Wireless Smart Cart, Wireless Spectrometer, and Wireless Weather Sensor

We are pleased to announce that PASCO has been awarded three “Best of Show” awards! More than two thousand science and STEM educators participated in the first Science Educators’ Best of Show™ Awards by casting their votes for products that they felt impacted science learning. We are honored to have our products recognized in a competition designed by science educators for science educators. You can check out the winners below!

Category: Best New Technology Innovation for STEM

Winner: PASCO’s Wireless Smart Cart and Accessories

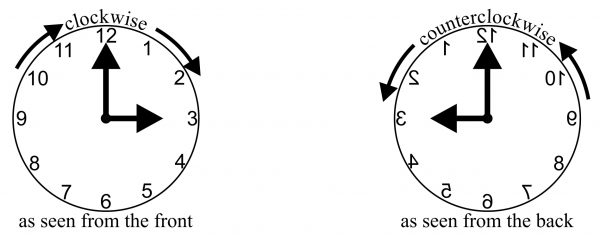

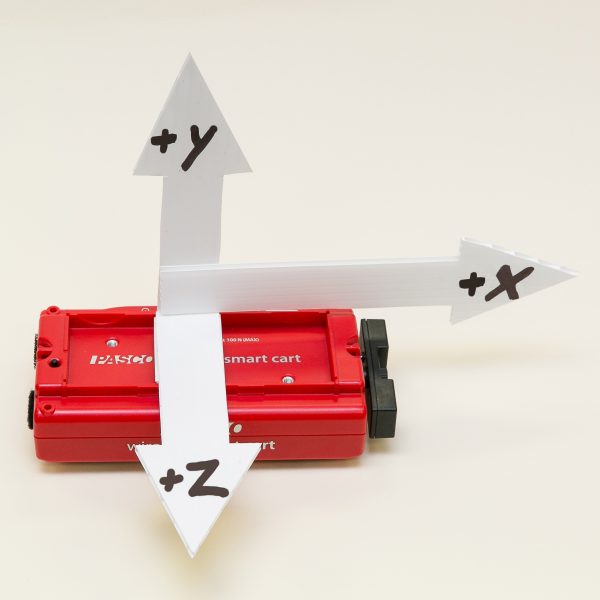

When physics educators combine the PASCO Wireless Smart Cart with the available accessories, they have a complete platform for demonstrating some of the toughest topics in mechanics. The Smart Cart’s ease of use and extensive capabilities allow students to perform their mechanics labs to a high degree of accuracy and repeatability. With sensors for position, velocity, acceleration, force, and rotation, the Wireless Smart Cart relays live data to help students test their understanding of mechanics in real time.

“The wireless nature of the PASCO Wireless Smart Cart and Accessories is a definite improvement [over traditional systems]. The removal of wires needed to connect to an external interface makes data more accurate and opens up opportunity for more innovative experimentation. The accessories for the carts also are very innovative and extend the scope of investigation.”

— Science Educators’ Best of Show Judge

Category: Best Tried & True Technology Teaching and Learning: Chemistry

Winner: The Wireless Spectrometer and Spectrometry software

With measurements for emission spectra, intensity, absorbance, transmittance, and fluorescence, the Wireless Spectrometer is surely more powerful than its size suggests. Its visual, user-centered design makes it easy for educators and leaners of all levels to integrate spectrometry into their learning. The key is PASCO’s Spectrometry software, which allows students to quickly generate standard curves, make comparisons, and analyze their results using its visual absorbance display. When combined, the Wireless Spectrometer and Spectrometry software provide educators with a classroom-friendly spectrometry solution that can be applied to a wide variety of chemistry topics.

“This device provides advanced analysis potential of spectrum analysis for chemistry, environmental and physics classes that is quite rare for high school classes to experience. The data collection is quick and thorough with excellent software for analysis on many devices. Use of this device and software will enhance learning in many science courses.”

— Science Educators’ Best of Show Judge

Category: Best Tried & True Technology Teaching and Learning: Environmental Science

Winner: The Wireless Weather Sensor and SPARKvue software

With more than nineteen different measurements, including GPS, the Wireless Weather Sensor supports real-world environmental investigations that relate phenomena to data collection and analysis within SPARKvue. Together, the Wireless Weather Sensor and weather features within SPARKvue create a coherent solution for performing both long-term and short-term environmental inquiry at any science level. The Weather Dashboard within SPARKvue intuitively displays live and logged data, while SPARKvue’s ArcView GIS mapping integration supports geospatial investigations and analysis.

“This sensor would provide extra opportunities for data collection in environmental science. It does offer a variety of options for experimental situations-19 in all. Experiments can be of short duration or long term. The weather vane is mentioned as an extra device to enhance data collection.”

— Science Educators’ Best of Show Judge

Sheridan College (Davis Campus) conducted their 3rd annual Skills Competition on March 4th, 2020, a day dedicated to recognize and celebrate the accomplishments of the students from various programs within the Faculty of Applied Science and Technology. Previously, professors selected their top students to compete in the Skills Ontario competition but with Sheridan’s new Skills Trade Centre, a more engaging way to select the students was brought forward.

Sheridan College (Davis Campus) conducted their 3rd annual Skills Competition on March 4th, 2020, a day dedicated to recognize and celebrate the accomplishments of the students from various programs within the Faculty of Applied Science and Technology. Previously, professors selected their top students to compete in the Skills Ontario competition but with Sheridan’s new Skills Trade Centre, a more engaging way to select the students was brought forward. AYVA was proud to be a sponsor for this years’ event. It was an honour to be able to witness the extraordinary projects presented by the students.

AYVA was proud to be a sponsor for this years’ event. It was an honour to be able to witness the extraordinary projects presented by the students.

The unit features an air-cooled condenser unit connected to an evaporator located in an air duct. The air duct contains relative humidity and temperature sensors on both sides of the evaporator. A small fan provides air flow down the duct and can be manually adjusted.

The unit features an air-cooled condenser unit connected to an evaporator located in an air duct. The air duct contains relative humidity and temperature sensors on both sides of the evaporator. A small fan provides air flow down the duct and can be manually adjusted.